Chicago Fed president Charles Evans wants to keep the federal funds rate at zero until the unemployment rate improves.

(Money Magazine)

As chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke takes questions from Congress and at press conferences; markets move on his words. Increasingly, he's also the target of public anger, whether for meddling too much in the economy or for not doing enough.

The Fed chairman does not, however, act alone.

The system he oversees (essentially, the bank for banks) sets policy with the votes of seven presidentially appointed governors, the head of the New York Fed, and a rotating group of four chiefs of the other regional Fed banks.

At a time when the Fed has trekked far past its traditional frontiers -- holding short-term rates near zero, buying up trillions of dollars in financial assets, and, in December, declaring it would keep all this up until unemployment comes down -- market watchers are also paying close attention to those other voices.

Related: Where will the next big bull market come from?

And some of those voices disagree. A lot.

On one side are the so-called hawks, who worry that more easing won't work, or that it could set up a risk of higher inflation in the long run.

On the other are the doves, who have backed Bernanke and sometimes cajoled him toward more aggressive efforts.

The stakes of this insiders' debate are huge. What the Fed does next, and whether it's right, will dictate the security of your retirement, the performance of your investments, and the stability of the economy all around you.

THE FED'S GREAT EXPERIMENT: Uncle Sam wants you... to spend

"These are scary times if you are an investor," says Janet Yellen, the vice chair of the Fed's board of governors. "We've been through the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression."

Yellen, 66, is frequently spoken of as a candidate to succeed Bernanke in the top job when his term expires in 2014 and is seen by Fed watchers as a leading dove -- a label she rejects, pointing out that she thinks the Fed must fight inflation too. The problem, from her vantage point, is that the past five years have been so wildly unusual that it has taken an equally unusual response for the Fed to have any hope of bringing things back to normal.

To understand the Fed's current high-wire act, start with what it does in normal times.

Congress has handed the Fed the twin responsibilities of keeping prices stable and holding down unemployment. The Fed's most visible tool for doing that is to adjust the short-term Fed funds rate, the interest banks charge one another for loans.

By making money easier to get, low rates can spur growth but pose an inflation risk if workers come to think they can bid up wages faster and businesses believe they can jack up prices. Higher rates can slow inflation, but they also stymie growth and employment. That much is business as usual.

When the bottom fell out of the U.S. economy in 2008, the Fed quickly cut rates down to near zero. Not business as usual. Also not enough. Unemployment touched 10% at its worst and remains frustratingly high. So the Fed has been experimenting. One name for its experiments is "quantitative easing," which has now been rolled out multiple times since the crash.

QE is partly an extension of a routine practice -- to adjust rates, the Fed normally buys and sells very short-term bonds. But with QE, it has also bought a massive pile of longer-term Treasuries and bonds backed by home mortgages.

Because this is the Federal Reserve, it buys using money created by a keystroke that adds dollars to the reserve accounts of the banks it trades with. The effect is to reshape the market for basically all financial assets.

Related: Bond investors, beware

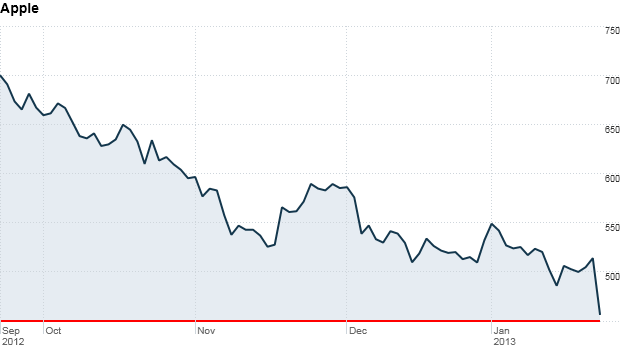

Buying up bonds pushes down longer-term interest rates, which ought to make it easier for businesses and homebuyers to get loans. It also makes low-risk assets like Treasuries less attractive to hold on to, hopefully getting money off the sidelines so companies invest and hire, home values rise, and consumers feel wealthier and spend. Bernanke has said that a rising stock market is an indicator that QE is working -- that investors are embracing risk. Since 2009, the S&P 500 has more than doubled.

The Fed, says Yellen, is trying "to make the environment more predictable, more favorable, and less scary." The weird irony is that to push toward this safer-seeming world, the Fed has had to make things harder on people who want to park their money someplace safe. These days a five-year CD earns less than 1%.

Untested as they are, the policies may well be propping up the U.S. economy at a time when Europe is floundering, Chinese growth is slowing, and American fiscal policy is tangled in partisan fights over budgets, taxes, and debt. The added drama here is that no one knows exactly what will happen when the Fed tries to return to normal.

Sometime in the next few years the bank will need to stop stimulating growth and start selling the assets it has accumulated along the way. No central bank has ever before unwound such a massive amount of stimulus.

The Fed "is making up a lot of this as we go along," says Tim Duy, a University of Oregon economist who writes a blog called Fed Watch that is popular among monetary-policy junkies. "We're not entirely flying blind from a historical perspective, but we're certainly close to that."

WHAT THE HAWKS FEAR: Does this thing go in reverse?

The most recent round of QE had just one dissenting vote, Richmond Federal Reserve president Jeffrey Lacker. This near unanimity doesn't reflect how hot the political passions around monetary policy are or how careful Bernanke and the doves have had to be in selling their policies.

The Fed's monetary committee isn't like the Supreme Court; it rarely issues sharply split decisions. Instead, Bernanke quietly builds support for new policy moves before announcing them. "In the Bernanke Fed, the most important thing is the process -- everyone gets to talk," says Michael S. Hanson, an economist and Fed watcher at BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research.

Outside the Fed, Bernanke has to consider increasingly hostile Republicans in Congress; their party's 2012 platform called for a commission to study a (seriously unlikely) return to the gold standard, taking much of the monetary power out of the Fed's hands.

Related: What to do in a market where anything can happen

Within the Fed itself, the critics include high-profile presidents of regional Fed banks. Although two of the most outspoken hawks, Charles Plosser of the Philadelphia Fed and Richard Fisher of Dallas, aren't on the monetary policy voting rotation this year, their opinions make headlines.

Like Bernanke, Plosser, 64, is an academic economist. He sees little evidence that the Fed's moves boost growth.

Declining home values, he notes, have wiped out a huge amount of household wealth. Americans are trying to rebuild that wealth. So the Fed's efforts to spark more consumption, he says, are just cutting against consumers' natural inclinations -- and may be hampering their efforts: "They don't want to spend," Plosser says. "They want to save."

Plosser also argues that there are risks to what the Fed has been doing. In buying all those long-term assets, the Fed has poured huge amounts of money into banks' reserves. Right now a lot of that money is just sitting there;

Plosser's worry is that the money could eventually pour too fast into the real economy, fueling inflation if the Fed doesn't act.

In theory, the Fed merely has to reverse the QE process, selling assets to suck up all those dollars. Easier said than done, says Plosser. "If we are too late or must react aggressively, the consequences could get more ugly, more risky than in normal times," he says.

Fisher, 63, is a former investment banker with a Stanford MBA, and he doesn't talk much like a Fed technocrat. In a recent speech he called members of Congress "parasitic wastrels" and quoted the country singer George Strait to extol the benefits of Texas's low-tax, low-regulation business climate. He's careful to say he doesn't see inflation right around the corner, but echoes Plosser's concern that the Fed can't create more growth from here.

"My view is we've done enough," says Fisher. "The gas tank is overflowing."

His criticism also has a moralist's edge: The Federal Reserve, he says, has "penalized those who played by the rules, saved money, and particularly those who are aging -- people like me, who are baby boomers, early baby boomers. Their returns have been driven down to nil." Fisher calls the recent stimulus efforts "monetary Ritalin."

NEXT: WHY THE DOVES DON'T QUIT

![]()